Opportunity to make up for defects

Mongolia began a digital transition using electronic ID cards to all citizens more than 10 years ago. The introduction of e-ID, which recognizes faces and fingerprints and contains all personal information, has created a reliable database for government agencies such as suffrage, taxation, customs, passports and defense agencies. However, regarding use, e-ID is not used at a sufficient level compared to the original Estonian digital ID. e-ID cards were first introduced in 2012 to promote public services and reduce administrative costs. Therefore, with the introduction of a “kiosk” device based on an electronic ID card, citizens can receive 19 types of inquiries and documents without visiting government agencies. The kiosk provides public services to 2,000 to 3,500 people on weekdays and 530 to 760 people on weekends. Recently, however, thanks to private-sector, e-IDs have become available for telecommunications and banking services. In addition to initiatives to digitalize public services, mobile operators, banks and financial institutions are rapidly digitalizing services. Start-ups in Mongolia have limited funding sources, but Itools LLC and LendMN NBFI have successfully raised equity markets. LendMN, in particular, is considered to be globally competitive.

In line with the requirements of the time, digital signatures were introduced in the banking sector in 2018 within the framework of the Digital Financial Services Project. Large banks have also launched mobile applications to simplify daily transactions and other banking activities.

According to a 2017 study by the Center for e-Business Development, more than 70 percent of consumers use mobile banking apps every day.

The banking and financial sectors are leading the private-sector digitalization process, and government-level registration and tax authorities’ technical reform has been active in recent years. For example, the tax information system has been upgraded and an electronic VAT refund system, E-barimt, has been introduced. The ebarimt system currently has 1.2 million users, a significant increase from 2016 when it had 496,000. “Developments vary from sector to sector, but good practices implemented in one sector should be used in other sectors,” said T.Batbileg, Director of the Technological Center of Customs and Tax Information. On the other hand, L.Hulan, Honorary Consul of Consulate of the Republic of Estonia to Mongolia, said “In Estonia, all public and private services are available if you have a mobile phone and an electronic ID”.

Today, government agencies and the private sectors, such as banks and mobile operators, offer services to citizens online, but these systems are separate. It is still difficult to exchange information from one organization to another. In short, “access” is lacking in Mongolian electronic migration.

Ready for online migration

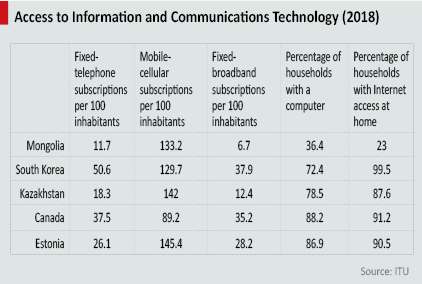

Are our basic infrastructure and environment ready to make e-government comprehensive? To answer this question, industry experts have released the Digital Readiness Assessment report. Today, 80 percent of the population is connected to the central power grid, while the remaining 20 percent live far away from the center of the province or soum, with limited access to electricity. Providing them with enough energy is expensive and difficult. According to the report of the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), Mongolia’s main advantage over digital access is the use of mobile phones. Mobile Internet access is a viable way to reach rural areas with poorly developed fixed information and communication infrastructure.

In terms of human resources, our university system is outdated and preparing engineers with little knowledge of new technology. For example, “Mobicom spends three years training new graduates to meet their job requirements,” said B. Soyolchimeg, the company’s human resources manager. According to the 2017 Employer Satisfaction Survey, 30.4 percent of new graduates are unable to complete job-related tasks, and 24.6 percent lack the knowledge and experience to complete their jobs. Also, when it comes to finding jobs, they are often low paid, leading to the departure of moderate and some skilled workers in developed countries such as Korea and Japan.

Regarding financial accessibility, the current financial system has not been developed to cover all areas of society. Commercial banks dominate the financial sector, and foreign banks are not allowed from doing business in Mongolia, weakening competition. While SMEs make up 90 percent of registered companies and 50 percent of employment, 90 percent of these organizations, or 36,800 companies nationwide, do not have access to bank loans.

From a legal perspective, Mongolia is one of the countries in the Asia-Pacific region, with the lowest trade and resource management systems and the lowest tax burden in the world. There are little direct government involvement in commodity markets and few state-owned enterprises.

In general, the legal system has important elements, but its enforcement capacity is weak.

According to police, as of 2017, 299 cyber crimes were registered nationwide. Cybercrime is not new, but there are currently no specific laws regarding the confidentiality of information. Electronic signatures are also a challenge for fintech companies. The legal basis for the use of electronic or digital signatures was established by the government in 2011 and is set out in other relevant laws. However, Bank of Mongolia and the Financial Regulatory Commission do not accept electronic signatures for banking operations, including contracts and transactions. Today, Mongolians are widely involved in local online shopping platforms and online shopping such as Amazon and Alibaba. However, the lack of a strong legal framework for online payments and individual payment systems makes it difficult to introduce e-commerce into domestic and international markets.

In addition to these basic infrastructure improvements, the main problem facing Mongolian society is the level of poverty. More than 30 percent of the population is below the poverty line, and another 20 percent are near poverty, with restricted access to the Internet in every way. According to statistics, one in three people has no financial means to buy the Internet or smart devices. Therefore, government need to plan its e-transition policies in a more comprehensive way to bridge this digital divide.