Robert van Zwieten: The use of blended finance can bridge the climate financing gap

Mongolian Economy Magazine spoke with Robert van Zwieten, the Managing Director at PwC Southeast Asia Consulting and Advisory Board of URECA, about climate financing to developing countries, blended finance and investor relations.

-Could you briefly introduce yourself to our readers?

-My name is Robert van Zwieten. I am a part-time Managing Director at PwC Southeast Asia Consulting in Manila, Philippines. I also run my own advisory firm. My work focuses on strategy, governance, sustainable finance, climate finance, blended finance and energy transition. I spent two decades working in global finance, capital markets and banking in Europe, the United States and Asia. I then transitioned to development banking, private equity in emerging markets and ultimately to consulting. In addition to that, I work as an Adjunct Professor in Finance at the Asian Institute of Management.

I was originally trained as a lawyer, at Leiden University in the Netherlands and at Columbia Law School in New York. Later, I got my MBA from the University of Chicago – Booth School of Business. In terms of my personal life, my wife and I have five children between 6 to 26 years old. What helps me to unwind is spending time with my kids, reading and riding my Ducati over the beautiful country roads of the Philippines.

-When did you first come to Mongolia? What ties you to Mongolia?

-I first visited Mongolia during 2011-2012 when I was working at the Asian Development Bank as the Director of the Private Sector Capital Markets. At that time, we were quite busy rolling out a large “Trade Finance Program” to counter the Global Economic Crisis. At that time, we enlisted all the major Mongolian banks in the program. We also met with the Central Bank of Mongolia to look into possibilities of lending and investing in commercial banks. I think Mongolia has some very interesting challenges to its inclusive and sustainable development. Somehow, the timing of my visits was always during the cold winters.

Later, I came back in 2017 for a brief visit and then again, very recently in August of this year. It was the first time I got a chance to see Mongolia in the summer. Currently, I am doing some advisory work for my clients in Mongolia. But, what really ties me to Mongolia is my business contacts and personal friends I have made over the years in Ulaanbaatar.

-What has inspired you to work towards advancing sustainable development through climate investments, capital mobilization and private capital investment in markets?

-There are two sources of inspiration, intellectual and emotional. My work in capital mobilization towards advancing sustainable development and climate finance started when I joined the Asian Development Bank back in 2009. Coming from the private sector, it was immediately obvious to me that the balance sheets of multilateral development banks are very finite. Moreover, the climate and development challenges are quite vast and complex. Thus, we needed to involve and mobilize private sector capital toward solving these challenges. That was initially not obvious to the rest of the people in the bank, but luckily, I won over a lot of minds. It also drew me to blended finance, a term coined only in 2015. It is a strategic use of public sector and/or philanthropic capital to mobilize private sector capital into SDG-related investments in emerging markets. That was the intellectual source of my inspiration. In terms of the emotional source, climate change is a huge global challenge for current and future generations – we are about to leave a much less habitable planet to our children and grandchildren. I think that’s not acceptable.

-What are the main financial instruments and mechanisms that are designed to assist developing countries in meeting their financial needs towards climate action?

-There are traditional instruments such as loans, equity investments, technical assistance and grants from development finance institutions. However, they are not flowing fast enough, and the scale of our interventions is still insufficient for the size of the problem. Globally, we need to invest much more and much faster so we can transition to cleaner renewable energy and retire coal-fired power plants in order to stay within the 1.5-degree Celsius boundary agreed upon in the Paris Agreement.

That’s where the private sector will need to come in, but they will start investing only if the risk-return profile of these investments makes sense to them.

They have a fiduciary duty to their pensioners, policyholders and many other stakeholders to be good stewards of their money. Last but not least, there is a concept called “Just Transition” which is aimed at leaving nobody behind in the energy transition and alleviating the socio-economic impacts of affected families and communities by reskilling (to green jobs), upskilling and investing in new job-creating opportunities in those regions.

-Many green projects in developing countries don’t meet investment risk management criteria. Hence, how can we mitigate the risks of those projects to enhance the flow of green finance to vulnerable communities?

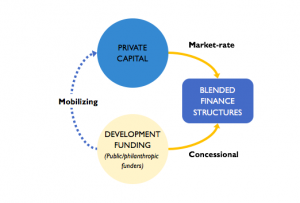

Source: Convergence

-We need to use blended finance techniques to mobilize private-sector investment. That requires a modest level of concessional financial involvement by the public sector and/or philanthropic capital to take risks off the table that the private sector finds very difficult and complex to deal with. For instance, a project development risk, political risk, off-taker risk, FX risk and other risks can be reduced and get absorbed through grant funding, insurance, or first-loss tranches in the financing structure. Once the private sector begins to see a reliable track record of well-performing transactions, they will need less and less concessional input into the transaction. Unfortunately, many developing countries have not put blended finance on top of their list. There is still a lot of capacity building needed amongst government agencies in order to be able to utilize the use of blended finance in developing countries.

-What are the main channels (organizations, institutions and etc) of blended finance for sustainable development in developing countries?

-A typical blended finance transaction has three participants: (1) the private sector institutional investor, (2) the public sector (government, multilateral development bank, or development finance institution), and (3) the philanthropic organization. Each has different motivations to sit at the blended finance ‘table’, their own return expectations, risk tolerances and level of financial sophistication. It is not easy to bring these parties together. Once you have managed to do that, the diversity around the table poses a “translational challenge”. There are very few organizations or intermediaries who have the necessary skill sets to pull together such a ‘next-level’ transaction. Not that a blended finance transaction is inherently all that complex – it just uses well-understood corporate finance techniques to shift around risks to the party best suited to bear them.

-Mongolia’s legal system and policy environment are considered the main barriers to climate finance due to its unclear, uncertain and contradictory nature. What recommendations would you give to Mongolia in attracting climate finance?

-Mongolia is not the only country that has such impediments to climate financing. In fact, many emerging markets have the same problem. It requires political will and sharp focus from the government side to solve this and to streamline the enabling environment to make it more conducive to the investments that the country needs for its sustainable future. The Mongolian people are very resourceful, adaptive and resilient. There is nothing they can’t do when they put their minds to it.

-What roles can central banks play in increasing the flow of green finance to developing countries?

-It will certainly need more than just the role of central banks to increase the flow of green finance to developing markets. I think they do have an important role to play when it comes to the local commercial banks that are subject to their supervision. Some Asian central banks have made good progress in “greening” their commercial banks and their portfolios. This may include reporting of “brown” financing and, later, higher capital charges on brown financing; training and capacity building within the bank on clean energy financing; adjusting operating and risk management processes; requiring a certain percentage of the portfolio at a date in the future to be qualified as green, and so on.

-Mongolia’s heavy reliance on coal continues to increase GHG emissions and air quality degradation. In terms of climate finance, what would be the best strategy for phasing out Mongolia’s coal-fired power plants and coal burning for heating in ger districts?

-The reality is that you can’t just early-retire coal-fired power plants and take them off the grid before you have phased in an equivalent amount of energy supply from clean and renewable energy facilities. That requires proper planning of new supply, clean energy investment programs and projections of energy demand. In Mongolia, clean energy projects are mainly financed by multilateral development banks, local banks and a few local conglomerates, but much more is needed.

There is a real opportunity for the ger districts to go solar together with ample battery storage.

I think it will make intermittent energy sources available for all. The ger district should also have its own “Just Transition” planning and implementation. No energy transition could be seen as successful, politically, socially, or economically, if it is not affordable, secure, inclusive and just.

-Under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, all nations are encouraged to achieve their NDCs through the use of internationally transferred mitigation outcomes (ITMO). How do you see the future of carbon credits?

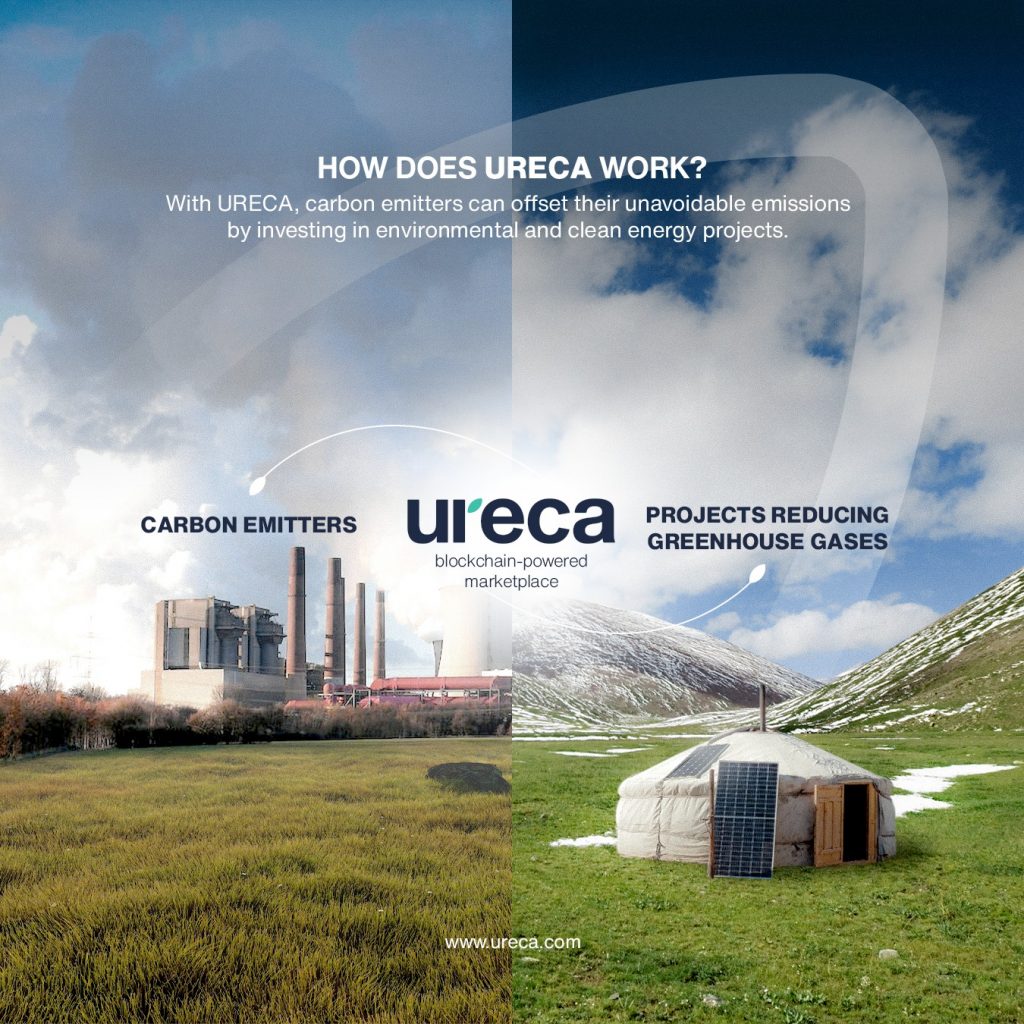

-In short, I don’t see a sustainable future and a stabilized climate without fully developed, efficient, well-regulated and liquid carbon credit markets. For any market to be successful and scaleable, it needs liquidity, standardization and a level of integrity so that market participants can have trust. The carbon credit markets are still plagued by low-quality credits and are fragmented. Moreover, it is costly and time-consuming for market participants to get their carbon credits certified. There are great initiatives underway to solve this problem. One of the most compelling ones comes from Mongolia, which is URECA, led by Orchlon Enkhtsetseg, a company where I serve on the Advisory Board. URECA is working to create an efficient and liquid global carbon credit market that is accessible to all, using Artificial Intelligence and Blockchain.

-Mr. Robert, you’ve conducted a business and led teams in the US, Europe and Asia for an extended period of time. No doubt that each country has its own market dynamics, business ethics and purchasing habits. Did it pose a challenge in conducting a business and leading a global team?

-I have found that people across the globe wish to be managed and led the way you yourself would ideally like to be managed and led. My philosophy is to lead with integrity, empathy and respect. Also, I always strive to lead by example, to empower people as much as I can and to guide them in their professional and personal growth. I closely manage or micro-manage only if, that’s really required. It’s okay for my team members to fail now and then because they can learn something in the end. Hence, I think as a manager you need to create a safe environment for them to do so. And then there is the art of delegation – you need to find the highest and best use of your time, talent and skills. On top of that, you need to be very clear about your priorities.

-You have a great deal of experience serving on public and private boards of startup companies. What are the key steps or criteria for building a successful fundraising strategy?

-That’s a big topic that would deserve its own interview! Ultimately, fundraising is about sharing the purpose of what you are doing or plan to do, and how you plan to do it, in such a compelling way that in the end, investors feel comfortable and confident to be part of your startup. If you would like to learn about this topic, a few years ago, I posted an article on LinkedIn on how to do fundraising more effectively for start-ups. (What good is your brilliant business idea if you can’t communicate it and win over institutional investors?)

-What are the common mistakes in maintaining investor and stakeholder relations among startups?

-It’s often hard for entrepreneurs/founders to build a business and be involved in a thousand moving parts at the same time, with little time and a constrained budget, AND find the time to communicate with investors and other stakeholders what’s going on in the business. Yet, it is critical that your investors and stakeholders can make that journey with you, and that you build more confidence in the quality and integrity of your leadership, the quality and speed of your thinking, the planning and the doing that goes into building your business. It is essential that you can celebrate and communicate milestones that get achieved. In tech startups, engineering skills often trump communication skills, so that sometimes can be a compounding factor.

-Mr. Robert, you’re quite well known for your ability to connect people from around the globe. Networking can be scary for many people and also it absorbs a significant amount of time and resources. What’s your tip for building and maintaining a professional network?

-Networking comes easily for extroverts like me, who are energized by connecting with people and listening to their stories. But I sympathize with introverts – I used to be one. Yes, it takes time and a bit of energy, but a genuine interest in what other people do, being ready to give and be generous with your assistance or contribution, and generally staying in touch, all go a very long way. I really enjoy connecting people who can help each other professionally, and that positive karma always seems to get returned to you in some mysterious and positive way.

-I find it interesting that you’re an Honorary Chair of Music for Life International. Why did you decide to join this New York-based social enterprise?

–Music for Life International’s mission is to create social transformation through the power of music. They organize and present musical concerts to raise awareness of significant humanitarian crises throughout the world. This social enterprise is led by a very dear friend of mine, who is an extremely talented conductor and artistic visionary, but he would not hold himself out to be a businessperson. I, on the other hand, would not profess to be a conductor or artistic visionary. So, we make a good team. I have been involved with Music for Life International from the very beginning. I also chaired the Board of Music for Life International for five years, at which point I felt somebody else should have a go at it, for good governance’s sake. Then they made me the Honorary Chair. It was a very kind gesture.

-Before we conclude our interview, is there anything you would like to say to readers of the Mongolian Economy?

-Climate change is our biggest challenge. Stay informed, learn the facts and make a difference!